Greetings

I. National Treasures of Japan - A Journey Through Art History

1. Masters of Japanese Art

2. The Splendor of Ancient Japan

3. Sacred Art

4. The Elegant Forms of Japanese Calligraphy

5. Japan and China

6. Samurai Art

II. National Treasures Highlighting Osaka’s History and Culture

The Tsumugu Project—Preserving Japanese Art for Future Generations

Thematic Exhibition: The Age of Expositions in the Imperial Collections

Thematic Exhibit

Greetings

This exhibition of National Treasures is the first of its kind to be held in Osaka as well as the first to be held at a municipal museum. Timed to coincide with Expo 2025, it was designed to serve as a cultural gateway for international visitors, enriching their experience by bringing them face-to-face with some of our nation’s greatest masterpieces. The exhibition features 135 National Treasures that trace the history of Japanese art while jointly shining a spotlight on those with ties to Osaka. The works on view date from the prehistoric to early modern period, and together, paint a rich picture of Japanese culture, inviting visitors from around the world to engage more deeply with our country’s heritage.

These works have survived for hundreds, and even thousands of years, despite Japan’s frequent natural disasters. This is thanks to past generations who dedicated themselves to preserving them. For us, our National Treasures embody the World Expo’s theme “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.” In that spirit, the exhibition also introduces conservation efforts that are preserving our cultural heritage for future generations. Another section looks at pieces shown in the 1900 Paris Exposition as well as Japan’s National Industrial Expositions to explore the relationship between National Treasures and expos. The works in that section were generously lent by The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan.

Beginning in the fall of 2023, our Museum closed for two and a half years for our first major renovation since opening in 1936. It is with immense pride that we open our doors again now to welcome visitors to this historic exhibition of National Treasures in our newly renovated galleries.

In closing, we wish to express our profound gratitude to the lenders of these invaluable works and to all those whose cooperation and support made this exhibition possible.

April 2025

Photo by Kosuke Sasaki

I. National Treasures of Japan - A Journey Through Art History

1. Masters of Japanese Art

Maple Tree By Hasegawa Tōhaku

Momoyama period, ca. 1592 (Tenshō 20)

Chishaku-in Temple, Kyoto

The works in this section were created by some of the most famous artists in Japanese history. In the medieval period, the Zen monk Sesshū Tōyō (1420–1506) traveled to China to master the art of ink painting, elevating the genre to new heights when he returned to Japan. During the war-torn Momoyama period (1573–1603), Kanō Eitoku (1543–1590) and Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539–1610) produced sweeping compositions for samurai castles, overpowering the viewer in both scale and style. As peace gradually returned, Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650) captured the bustling energy of Kyoto, and Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) produced bold, sophisticated designs that remain immensely popular today. In the eighteenth century, artists like Ike no Taiga (1723–1776), Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800), and Urakami Gyokudō (1745–1820) broke away from tradition, developing their own unique styles.

These iconic masters produced powerful works of art that continue to offer critical historical insights while inspiring viewers with their profound artistry.

2. The Splendor of Ancient Japan

Deep Vessel with Flame-Style Pottery

Middle Jomon period ca. 5400–4500 cal BP

Tokamachi, Niigata (In the care of the Tokamachi City Museum)

The art of ancient Japan is full of unexpected forms and designs. Early artists carved out a unique space for themselves, producing works that built on the archipelago’s existing cultures while also incorporating influences from abroad.

These included archaeological artifacts with distinct expressions and expansive forms, like a clay figurine (dogū) known as the “Jōmon Venus” and a famous pot with flame-like ornamentation along its rim. Later, advanced metalworking techniques brought from the Asian continent gave rise to works like the gilt-bronze saddle fittings found at the Fujinoki Tumulus.

Over time, Japanese art evolved to favor ornate designs and a sophisticated use of color. This aesthetic is seen in lacquerware objects decorated in powdered gold (maki-e) and textiles dedicated to Kasuga Shrine and Kumano Hayatama Shrine. The timeless artistry of these early masterpieces continues to fascinate people from all walks of life.

3. Sacred Art

Sutra Box with Composite Floral Motifs (Hōsōge)

Buried at the Nyohōdō Hall in Yokawa on Mount Hiei

Heian period, 1031 (Chōgen 4)

Enryakuji Temple, Shiga

The two primary religious traditions in Japan are Shinto and Buddhism. Since its introduction in the mid-sixth century, Buddhism in particular has inspired the creation of countless works of art in diverse genres, including sculptures, paintings, illustrated handscrolls, decorative arts, and hand-copied sutras.

This section introduces some of the most revered sacred treasures from each period of Japanese history. Buddhist paintings from the Heian period (794–1185) reflect the sophisticated elegance favored by courtiers of the day. Illustrated handscrolls of the six realms of transmigration, like the Hell Scroll, depict the misery of being trapped in an endless cycle of rebirth. Decorated sutras were given ornately illustrated frontispieces, and handscrolls were made depicting miraculous tales with distinctly human elements. Each work is a tangible expression of faith, embodying the hopes and prayers of people throughout history. The ornate and powerful forms they left behind are an enduring testament to the sincerity of their belief.

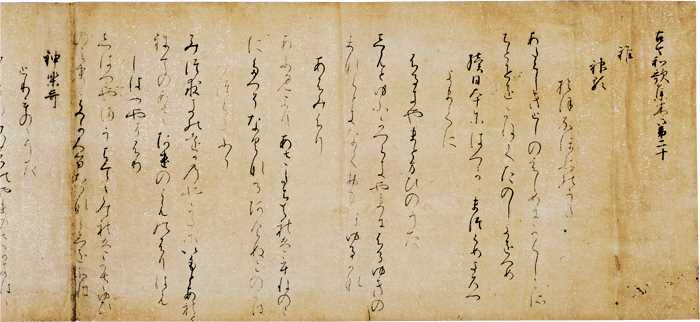

4. The Elegant Forms of Japanese Calligraphy

Collection of Japanese Poems Ancient and Modern, Vol. 20 (First Calligraphic Style of the Mount Kōya Fragments)

Attributed to Ki no Tsurayuki

Heian period, 11th century

Kochi Castle Museum of History

The art of calligraphy was introduced to Japan alongside Chinese characters. Early examples include Buddhist scriptures, called sutras, which were hand-copied in large numbers as Buddhism spread outward from the imperial court. Exceptional sutra manuscripts have survived from the eighth century that emulate calligraphic styles from China’s Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties. In the ninth century, calligraphers known as the “three brushes”—namely, the Buddhist monk Kūkai, Emperor Saga, and the court official Tachibana no Hayanari—are famous for mastering the styles of renowned Chinese calligraphers like Wang Xizhi (4th c.).

Around the tenth century, Japanese cultural practices based on Chinese precedents began to flourish in their own right, including the art of calligraphy. Courtier-calligraphers known as the “three brush traces”—specifically, Ono no Michikaze, Fujiwara no Sukemasa, and Fujiwara no Yukinari—are credited with creating, developing, and perfecting Japanese styles of calligraphy. At the same time, a writing system using Chinese characters to represent Japanese phonetically (man’yōgana) was replaced with domestic Japanese kana syllabaries. Among these, the hiragana syllabary in particular allowed for flowing calligraphic forms, as it was based on Chinese characters written in cursive script. These changes, together with the development of waka poetry and other literary modes, led to a flowering of Japanese calligraphic styles marked by their elegance and sophistication. The works in this section were brushed by some of history’s most celebrated calligraphers, offering an extraordinary introduction to the world of Japanese calligraphy.

5. Japan and China

Minamoto no Yoritomo (Purportedly)

Kamakura period, 13th century

Jingoji Temple, Kyoto

Ink painting was introduced from China along with the Zen school of Buddhism during the medieval period. Zen monk-painters at Shōkokuji Temple, like Josetsu, Shūbun, and Sesshū, are credited with developing unique Japanese expressions in the medium and are associated with its peak in Japan during the Muromachi period (1392–1573). As a Chinese art form, ink painting was framed in juxtaposition to yamato-e, a traditional Japanese style in colored pigments.

Within yamato-e, a genre of portraiture emphasizing individual facial features called nise-e was used to capture the likenesses of emperors. In contrast, portraits for members of the warrior class incorporated realistic depictions rooted in Chinese painting. The prominent Kanō school of painting emerged in the medieval period as well, originally focusing on Chinese styles but also later integrating traditional Japanese modes. Further cementing China’s influence, Japan’s ruling elites were avid collectors of masterworks from the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties, forming an aesthetic standard that lasted until the early modern period.

The works in this section explore Japanese and Chinese styles of art, inviting viewers to enjoy dueling performances by the most skilled artists of each genre.

6. Samurai Art

Armor (Ōyoroi) with Red Leather Lacing

Heian period, 12th century

Okayama Prefectural Museum

Today, samurai swords and armor are iconic symbols of Japanese culture around the world. The warrior class took special pride in their weapons, with some legendary swords even believed to possess supernatural powers. Samurai blades and military attire are masterworks of Japanese craftsmanship, seamlessly integrating advanced techniques in metalwork, lacquerware, and leather processing. This section explores histories of ownership, schools of swordsmithing, and the distinct forms found in samurai art.

Many celebrated swords date to the Kamakura period (1185–1333), an era marked by the advent of shogunate rule and the rise of the warrior class. Swordsmiths were based in key provinces, like Yamashiro (now Kyoto), the imperial capital, and Yamato (now Nara), a major religious center. Sword production also flourished in Bizen (now Okayama), thanks to readily available iron ore in the Chūgoku Mountains and convenient waterways for trade. The smiths in each of these regions came to be known for distinct traits. This exhibition highlights works by Hisakuni of the Awataguchi school of swordsmiths in Kyoto, Ryūmon Nobuyoshi from Nara, and the smiths Nobufusa and Sukekane from Bizen.

Unlike steel swords, sword mountings and armor were made of more fragile materials. Early examples of such works are far less numerous. Those from the Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura periods are particularly valuable. Most well-preserved pieces were handed down at Shinto shrines, like Mounting with Chinese Lions and Blade for a Long Sword (Kenuki-gata Tachi) and Armor (Dōmaru) with Black Leather Lacing, but rare examples from private collections have survived as well, like Armor (Ōyoroi) with Red Leather Lacing.

II. National Treasures Highlighting Osaka’s History and Culture

During the Kofun period (ca. latter 3rd c.–7th c.), Naniwazu port in Osaka Bay was an important gateway for trade with East Asia. It allowed the nascent Yamato court to access the continent’s latest technologies and Buddhist practices, which were then disseminated across Japan. In subsequent periods, Osaka remained a key port for trade with East Asia as well as domestic trade among provinces. Over time, the city became an economic and cultural powerhouse. Osaka’s historical importance is further underscored by the sheer number of National Treasures housed in its shrines and temples.

In the modern period, many of Japan’s cultural masterpieces came under threat of destruction, theft, or sale overseas amidst anti-Buddhist movements in the late 1800s, the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, and the turbulent eras that preceded and followed World War II. To protect the city’s cultural heritage, many of Osaka’s business leaders spent substantial sums of their own money to purchase historical works. Today, many of these can be viewed in the prefecture’s unique museums and libraries where they are preserved.

To celebrate Osaka’s first exhibition of National Treasures, this section presents works highlighting the region’s rich history and culture.

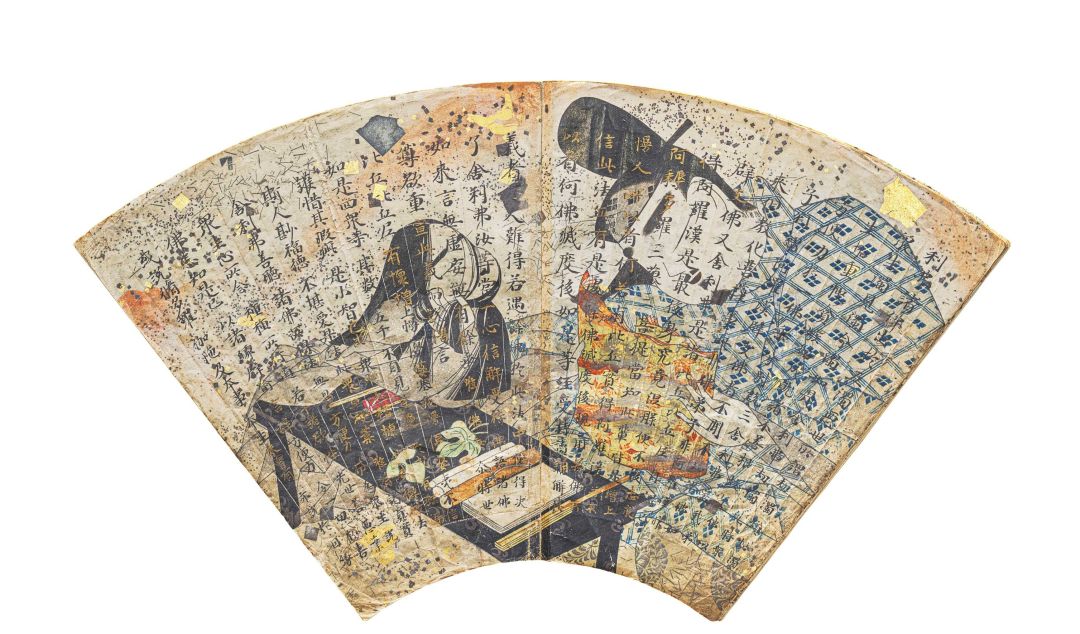

The Tsumugu Project—Preserving Japanese Art for Future Generations

Photo by Shirono Seiji

This exhibition was organized as part of the Tsumugu Project, a collaborative effort to preserve Japanese art by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, the Imperial Household Agency, and The Yomiuri Shimbun.

A cornerstone of the project is sponsoring conservation to halt deterioration and preserve cultural heritage for future generations. By the end of 2025, the project will have funded the conservation of fifty National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties since its launch in 2019.

In this exhibition, the following recently conserved works are being shown together for the first time: Bound Fan Papers with the Lotus Sutra (Shitennōji Temple, Osaka), Black-Lacquered Mounting for a Straight Sword (Chokutō) (Kashima Shrine, Ibaraki), and Document Soliciting Donations for Sennyūji Temple (Sennyūji Temple, Kyoto). Photographs showing the conditions of these works before and after conservation are on display as well, offering a close-up look at the techniques used to repair them.

A portion of the proceeds from this exhibition will go to the Tsumugu Project’s future conservation initiatives as part of our ongoing effort to highlight the importance of cycling between conservation and exhibition.

Thematic Exhibition: Masterpieces from The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan—A Legacy of Expositions

Bugaku Dancer Performing Taiheiraku (Dance of Peace)

By Unno Shōmin

1899 (Meiji 32)

The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan

Expositions held both domestically and internationally played a significant role in Japan’s modernization. These events not only showcased Japan as a rising modern nation but also served as platforms for promoting culture and industry, with many artworks on display.

The Imperial Household has had a strong connection to these expositions as well. For example, all the works presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition were created under the commission of Emperor Meiji. At domestic exhibitions, the emperors and members of the Imperial Family visited the venues and purchased artworks. These "imperial purchases" further motivated artists and sparked public interest in the arts.

The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan, which houses works associated with the Imperial Family, preserves many of these exhibition pieces. Each work represents the accomplishments of prominent artists and important eras, offering a valuable perspective on the pivotal role these international events played in the history of Japanese art.

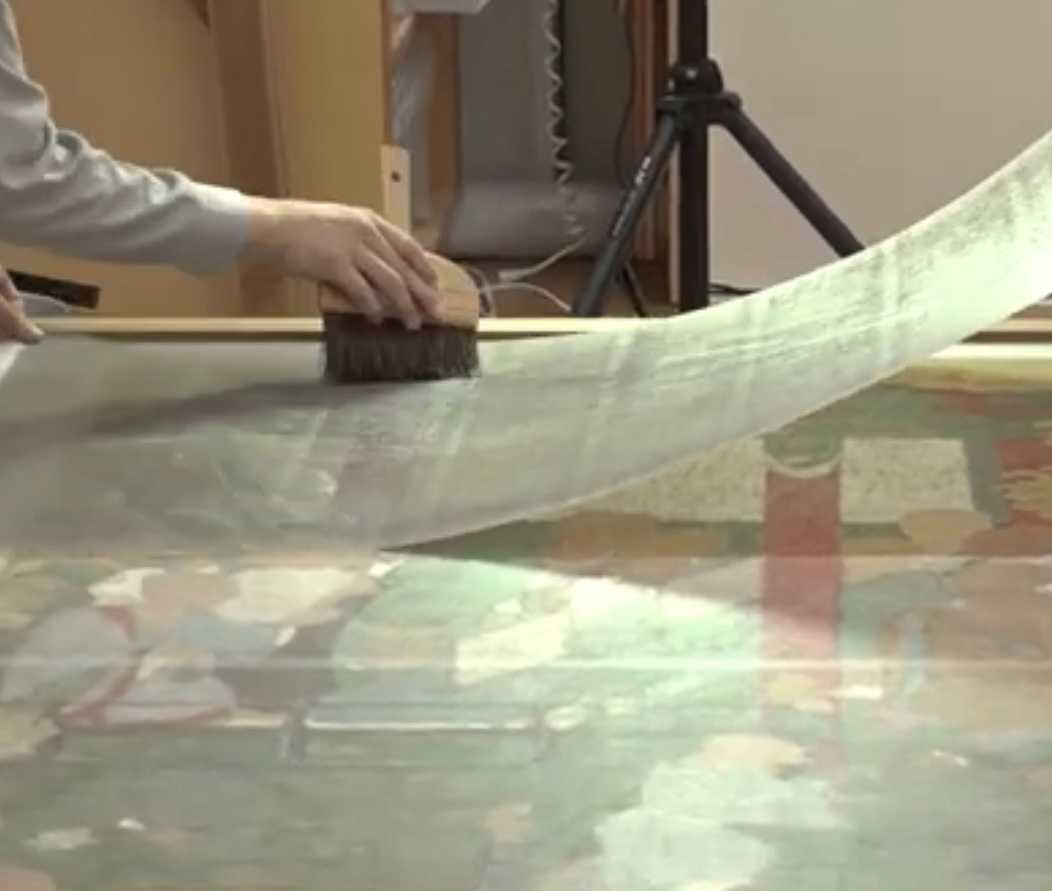

Thematic Exhibit: Conservation Techniques for National Treasures: Initiatives by the Agency for Cultural Affairs

Movements to preserve National Treasures first took shape in Japan in the nineteenth century, the same period as when World Expos (Expositions Universelles) began to be held in Europe. The gradual recognition that such works were important historical materials and artistic standards led to laws protecting them during the Meiji era (1868–1912).

These laws aimed to safeguard National Treasures from being sold abroad, damaged, or destroyed in fires. As society transitioned to mass production, however, traditional forms of craftsmanship began to be lost. These techniques were critical for conserving cultural heritage, and without them, it would be impossible to repair National Treasures. In response, the government introduced a designation for Selected Conservation Techniques in 1975.

Today, the government continues to implement a range of initiatives to ensure conservation techniques are passed down and that necessary tools and materials can still be procured. This section explores the world of traditional craftsmanship while highlighting the initiatives of the Agency for Cultural Affairs.