Brewing process

In early October, as the Suwa Basin fills with cold autumn air and the newly-harvested rice comes in, activity quickens at Masumi’s two breweries. Let us give you a tour of the seven months from October until April, when the master brewers and their staff watch over the brewing process with all the love, care, and strict discipline of parents for a beloved child.

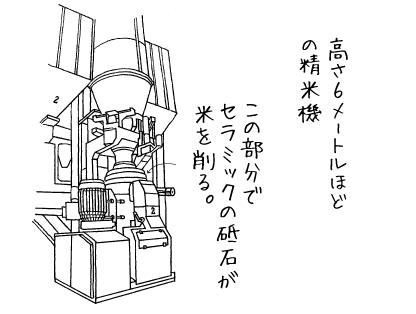

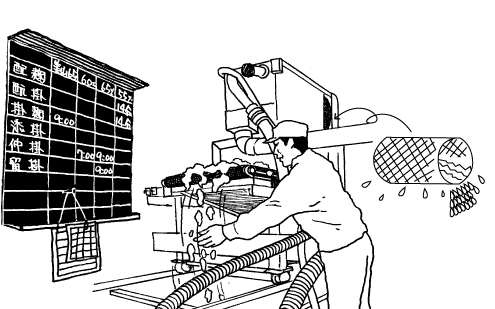

1) Polishing

The more you polish, the lighter and finer the taste.

The first step in our brewing process is to polish the rice in our own polishing plant. We do this to remove the outer layers of the grain, which contain an abundance of vitamins, fats, and protein. It is especially important to reduce protein, because during fermentation protein breaks down into amino acids that can taste bitter. More polishing results in lighter, cleaner tasting sake.

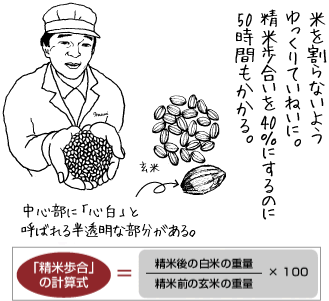

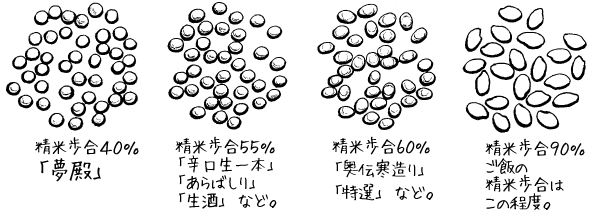

We know how much we have polished by comparing the weight of the brown rice before polishing to the weight after polishing. We indicate the polishing rate as a percentage remaining after polishing; for example, a polishing rate of 60% means that 40% of the rice was polished away, and 60% remains to be made into sake.

Note that the polishing rate is used to officially designate the grade of sake according to Japanese tax law. To be labeled DAIGINJO, super premium, the rate must be lower than 50% remaining, and to be labeled GINJO, premium, the rate must be between 50% and 60% remaining.

Polishing too fast breaks the kernels and over-heats the rice, so this work must be done slowly and gently. It takes more than 50 hours to achieve a polishing rate of 40%.

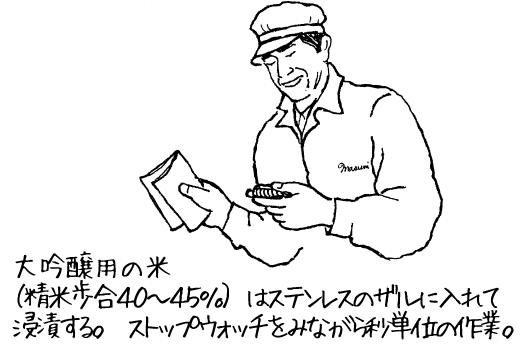

Over-soaking turns all efforts to froth.

After polishing, the pearl-like rice is transferred to the brewery, where it is washed and soaked. Although the purpose of soaking the rice is simply to allow it to absorb the desired amount of water, achieving just the right water content is easier said than done. The more the rice has been polished in the previous step, the faster it will soak up water. If highly polished rice is carelessly left to soak for too long, it will become too soft during steaming and cannot be used to produce fine sake. To avoid this, our brewers use stop watches to time the soaking down to the minute, and continually modify the design of the soaking equipment to achieve the best results.

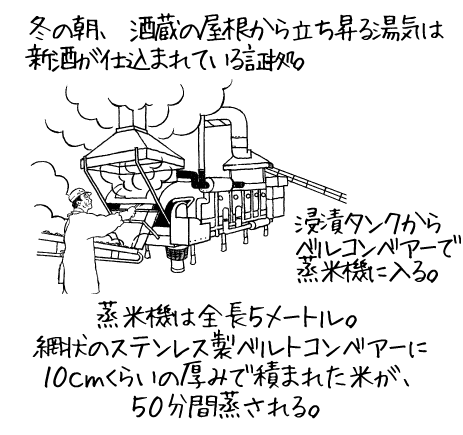

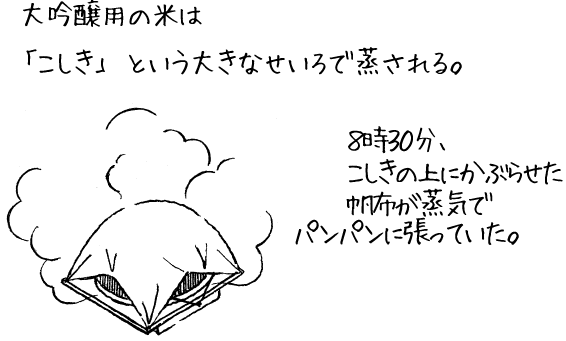

Firm outer surface, soft center.

Early the next morning, the rice that was soaked the previous day is steamed. In order to make ideal koji (rice malt) and to ensure proper fermentation of the mash, the rice kernels must be steamed in a way that results in a firm outer surface and a soft inner core. The same care given to soaking the rice is also devoted to steamingーtemperature and pressure are precisely controlled and the steaming equipment is constantly being adjustedーall to achieve this magic combination of firmness on the outside, and softness within.

4) Koji making

The heart of the brewing process.

Sake may seem similar to wine in appearance and taste, but the way it is fermented is actually closer to beer, because the raw ingredients of beer and sake are starchy grains, not sugary fruits. Yeast cannot eat starch, so the first step in making beer and sake is to break down the starch into sugar that the yeast can eat and turn into alcohol.

For sake, the rice starch is broken down to sugar with the help of a fungus called koji. When the koji fungus is grown on steamed rice, it creates the enzymes needed for this magical conversion. How the koji is grown strongly influences the flavor and quality of the sake, so great care is taken during the two days required to cultivate it. The brewers apply a combination of science and hard-earned skill to raise each batch of koji with all the care you’d lavish on a new-born baby.

Day one.

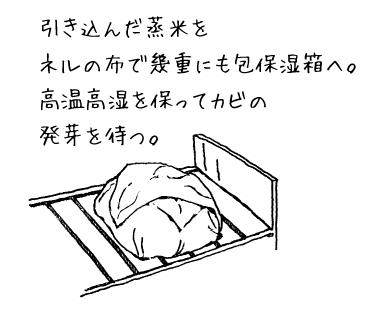

On the first day of koji making, a 20% portion of the rice steamed that day is moved into the koji room and sprinkled with powdery koji spores.

In the afternoon, the batch is hand-mixed to spread the heat evenly.

Day two.

On the morning of the second day, the koji is moved into a special box called a tana. The koji is now said to be at its peak. In the afternoon the koji is spread thinly on a heated table to aid in evaporation. Great care is taken to avoid sudden rises in temperature. At about 7:00 in the evening this process is complete and the koji is given its final handling.

Day three.

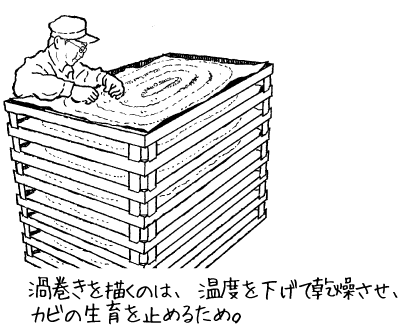

On the morning of the third day, the steaming koji is taken out of the koji room into the cold brewery. The brewers then spread the koji in swirling lines on trays. The perfectly cultivated koji, packed with the enzymes needed to break starch to sugar, is ready to be added to the various fermentation tanks.

5) Starting fermentation

Sake’s mother: shubo (yeast starter)

When the koji rice malt is ready, it is time to start yeast fermentation. The first step is to cultivate a robust yeast culture in a small tank. This yeast starter is called the shubo, which literally means “sake’s mother.” Once this starter mash is thriving, it will be moved to increasingly larger tanks and the volume of the mash will be increased by adding more water, steamed rice, and koji.

To create the yeast starter, warm water, koji rice malt, lactic acid, yeast, and steamed rice is added to a small tank. Enzymes in the koji begin breaking down starch to sugar, and the yeast start to multiply as they consume this sugar. Keeping the sugary mixture free from unwanted microbes, and keeping the yeast from producing too much alcohol too quickly, is no easy job. A pristine environment must be maintained and the starter temperature must be strictly regulated over the fourteen days required to develop the yeast culture. If this process is carried out properly, the result is a culture with two- to three-hundred-million thriving yeast cells in every drop.

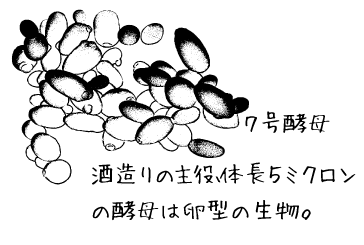

Little giants: sake yeast

A sake yeast cell is only about 5 microns in length. Yet this tiny organism performs the invaluable service of turning sugar into alcohol. There are countless varieties of yeast out there in the world, but they don’t all have the magical ability to produce fine sake. Until the Meiji period (1868-1911), brewers made a lot of mistakes because they lacked the science needed to identify the best yeast strains. In 1905, a national system of sake-brewing research centers was established to identify superior yeast varieties and to promote their use by the nation’s sake brewers. Each newly discovered variety was given a number, and was then distributed by the national brewing association. Thanks to this “Brewing Association Yeast” program, the quality of sake has increased by leaps and bounds.

Masumi’s famous yeast number seven

In 1946, Masumi swept the top awards at the regional and national sake appraisals, which got the attention of the brewing institute’s yeast scientist, Dr. Shoichi Yamada. Dr. Yamada visited the brewery and confirmed the presence of a very fine yeast in the fermentation vats. Masumi’s yeast was named “Brewing Association Yeast Number Seven”, and it soon became the favorite of brewers across the nation. Even today, number seven is the most widely used sake yeast in the world.

6) Increasing the mash

Increasing the mash in three stages is a brewing fundamental.

In the two weeks since starting fermentation, the yeast has grown into a robust culture, and it is time to begin increasing the volume of the fermenting mash by adding more water, koji rice malt, and steamed rice. However, bringing the mash to full volume all at once once would weaken the yeast culture, so these ingredients are added in three stages over the course of four days. Gradually increasing the volume of the mash in three stages is one of the fundamentals of good sake brewing.

Day two= “Odori” (a day of rest: nothing added)

Day three= “Naka” second addition (koji + steamed rice + water)

Day four= “Tome” third addition (koji + steamed rice + water)

To make good sake, you can’t pamper the brew.

When the mash reaches its full volume of about 2.5 tons of rice and four tons of water, fermentation begins in earnest. The enzymes of the koji continually convert starch to sugar, which the yeast then consume, and in the process, produce alcohol and the essences of the sake’s fragrance and flavor.

The most important element for proper fermentation is undoubtedly temperature control. From the yeast’s point of view, the most comfortable temperature is around 28°C, but at that temperature the yeast would grow too rapidly, producing only alcohol then dying before the fragrances and flavors are developed. Keeping the temperature of the mash below what is optimum for the yeast is absolutely essential for producing fine sake. Indeed, just as with children, over-pampering the brew will prevent it from reaching its full potential.

7) Filtering

Filtering the sake must be slow and gentle.

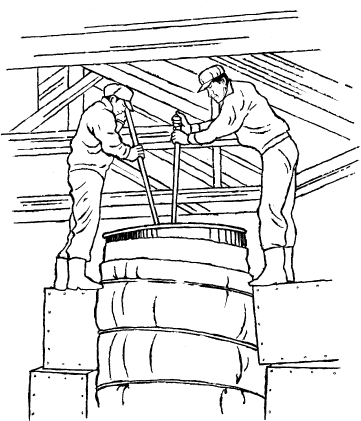

After about 25 to 30 days, the mash so carefully fussed over by the brewery workers has reached 16% to 19% alcohol, the aromas and flavors have fully developed, and the mash is ready to be filtered. We use three methods for filtering, depending on the quality and the quantity of the sake. We filter super-premium sake made for competition by pouring the mash into cloth bags, which we then drip into tanks. For some super-premium products, we stack these same cloth filter bags in a deep tub called a “fune” and apply gentle pressure. For sake we make in larger volumes, we use filtering machines that employ compressed air to very gently press the mash through cloth panels.

With the exception of limited seasonal varieties that are bottled and shipped right after filtering, most sake is aged in tanks or bottles for between six months and a year before it is sold. Depending on the style of the sake, a variety of post-filtering techniques may be applied before final packaging, such as micro-filtering with charcoal, pasteurizing, and diluting with water to lower the alcohol content.